From Detroit’s Walk to Freedom to the March on Washington: 60 years of civil rights legacy

Aug 24, 2023

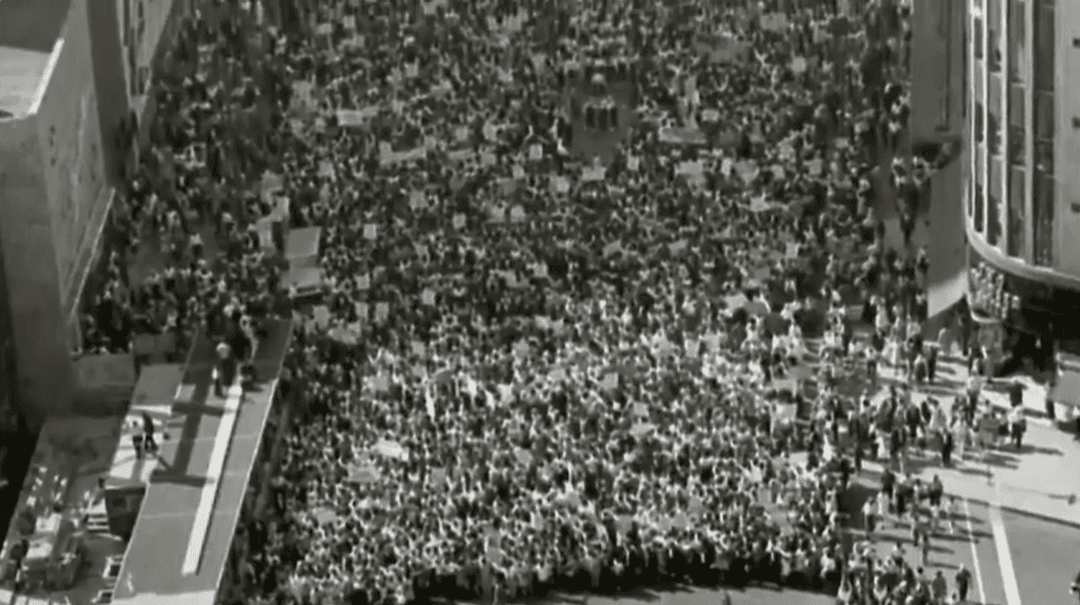

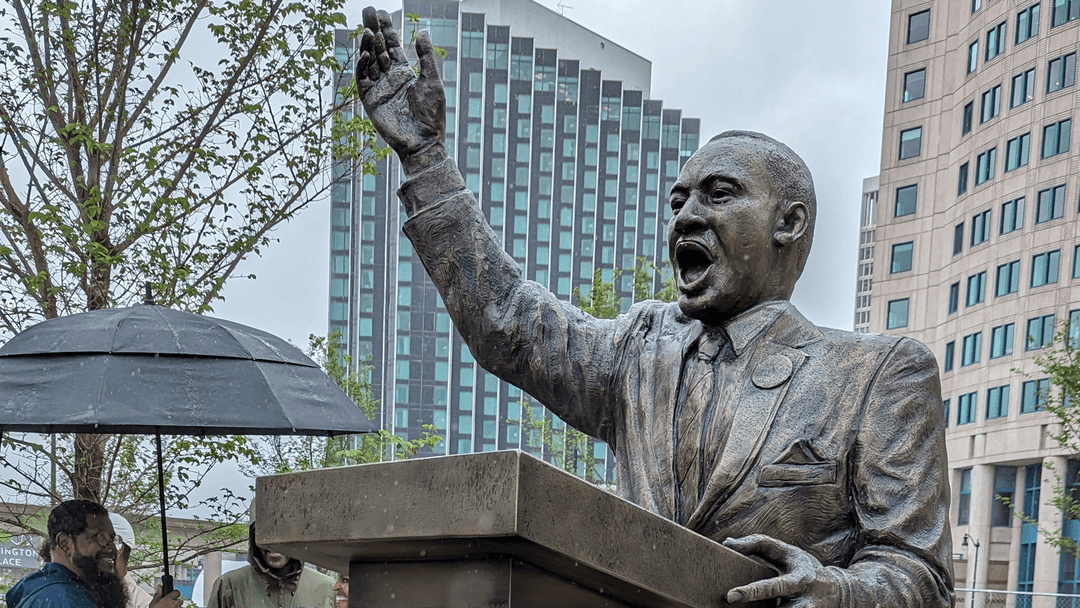

As the nation commemorates the 60th anniversary of the historic March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, a pivotal event in the civil rights movement, attention turns to the significant role that Detroit played in shaping this transformative moment. The march, renowned for Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s iconic “I Have A Dream” speech, not only symbolized the quest for equality but also marked a turning point in the fight for civil rights.

Reflections on the powerful connection between Detroit and Dr. King come to the forefront as local leaders, historians, and communities celebrate the indelible impact the 1963 Detroit Walk to Freedom just two months earlier had on the historic Washington March.

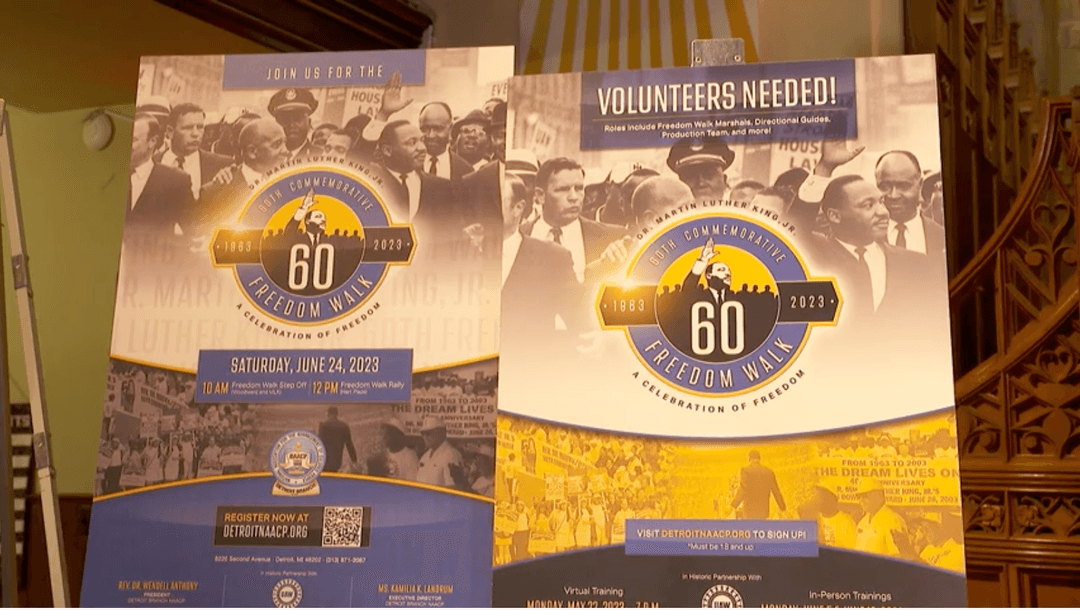

RELATED: Explore One Detroit’s coverage of the Detroit Walk to Freedom 60th anniversary events

Both events spotlighted the collective will of countless individuals who demanded an end to racial injustice and inequality. Through peaceful protests and Dr. King’s eloquent call for racial harmony, both marches galvanized a generation, spurring legislative reforms that would resonate for years to come.

The presence of influential figures in Detroit such as the Reverend C.L. Franklin and Rev. Albert Cleage, Jr. and the support of the United Auto Workers (UAW) union under Walter Reuther’s leadership, helped solidify the momentum needed for the Civil Rights Movement.

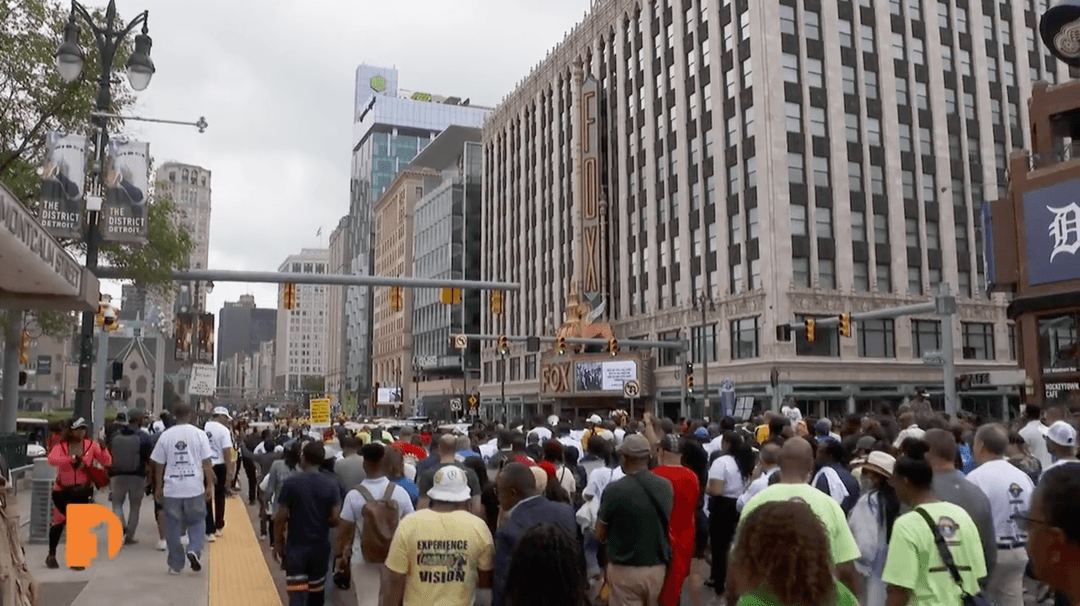

At a commemorative march two months ago, hundreds of Detroiters honored their legacy by walking down Woodward Avenue — a living testament to the courage and resilience displayed during those transformative years six decades ago. The echoes of the 1963 events still flow through the streets, and the spirit of Detroit’s Walk to Freedom lives on as the next generation of residents relive and memorialize this history.

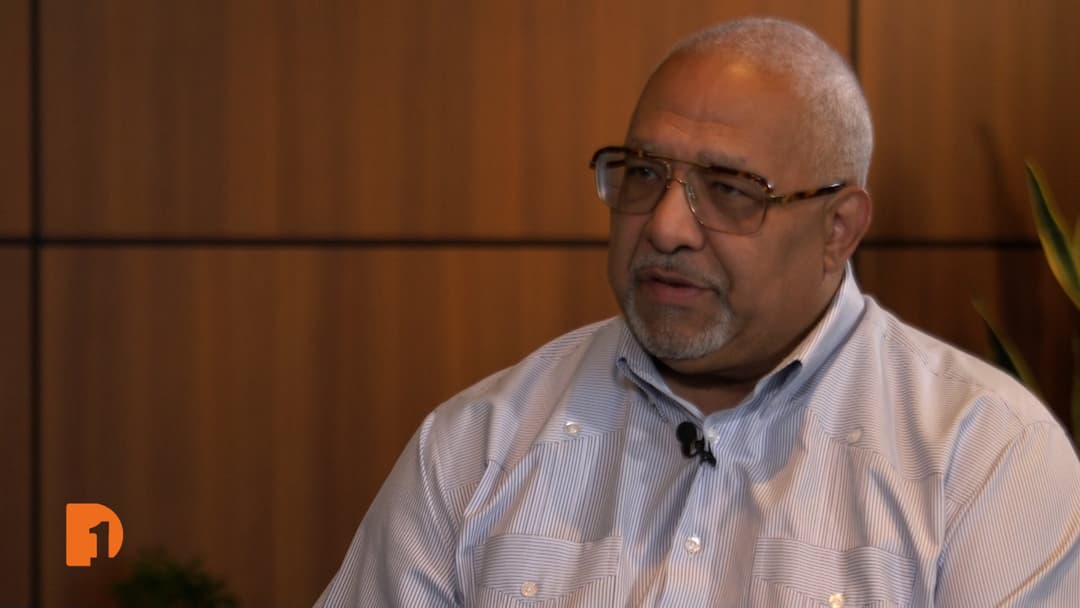

One Detroit Senior Producer Bill Kubota explains the tie between these two historic events and how they changed civil rights in America.

Full Transcript:

Bill Kubota, Senior Producer, One Detroit: The 1963 march led by Dr. Martin Luther King and that “I Have a Dream” speech in Detroit commemorated two months ago along Woodward Avenue. Hundreds taking part.

Leon Russell, Chair, NAACP National Board of Directors: I hope that as you step out into the street this morning, you are making a commitment, a commitment to organize our community.

Lt. Governor Garlin Gilchrist II, State of Michigan: It’s a generational moment and it’s personal for me. My father marched 60 years ago as a six-year-old in this march.

Shawn Fain, Detroit, United Auto Workers: Organized labor and the civil rights movement are inextricably intertwined. We stand together and it is a great, great, prestigious honor to be a part of this.

Lt. Governor Garlin Gilchrist II: We see people banning books. People want to ban the book that talks about Dr. King. This march would not be acceptable in Florida under the current government, under the current legislation.

Teferi Brent, Community Activist: You can never stop marching. It’s critically important that we have fixed policy to protest. Protest without policy is pure performance.

Bill Kubota: The fight now? The fight back then. Then it was the Walk to Freedom, Detroiters, and Dr. King. Historic. Some say the beginning of a change that was going to come.

Orlando Bailey, Engagement Director, BridgeDetroit: Why is it a little-known fact that Dr. King rehearsed the “I Have a Dream” speech here in the city of Detroit first before he took it to D.C.?

Dr. Michael Eric Dyson, Professor, Author and Activist: Well, you know how it is, man. You’re getting your sing on at one place before you go sing-

Orlando Bailey: You’re working it out?

Dr. Michael Eric Dyson: That’s right. You’re working out the kinks and stuff. And this ain’t no small place, Detroit. If you can do it in Detroit, then you can withstand all kinds of critique because people here are rigorous about performance, about intelligence, about oratory and the like.

Orlando Bailey: Charity, you were intentional with bringing your daughter here. Why?

Charity Dean, CEO, Metro Detroit Black Business Alliance: Well, she has to see this in action. And she also gets to see mom at work in a number of ways. She also needs to see mom marching down and she needs to get the opportunity so that ten years from now, 20 years from now, 30 years from now, she will be able to say she participated in the march as one of the first steps toward her own fight for freedom for all of us.

Gregory Gunn, Retired DPSCD Teacher: This is commemorating the Detroit downtown walk from Woodward to Cobo Hall in 1963. I was six years old when I was in the first March in 63.

Orlando Bailey: You were in the original march in 1963-

Gregory Gunn: My dad brought me.

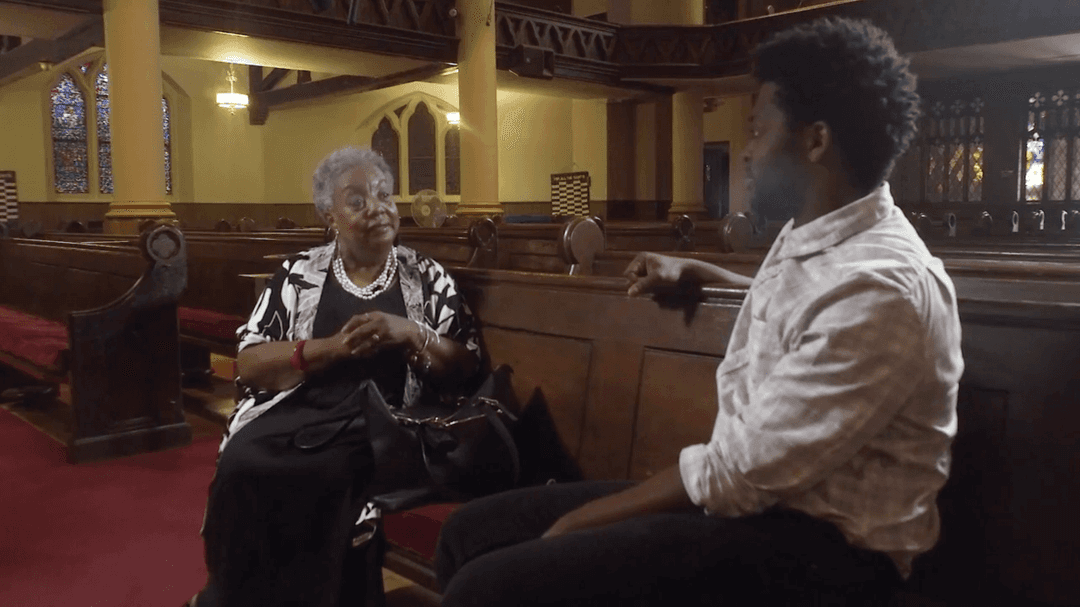

Bill Kubota: Memories 60 years on for Gregory Gunn and for Dorothy Dewberry Aldridge.

Dorothy Dewberry Aldridge, Civil Rights Activist: It was a beautiful, beautiful day. And no one expected these many people to show up.

Bill Kubota: An estimated 125,000. Aldridge was 20 years old in 1963. She’s talking with One Detroit contributor, Bryce Huffman.

Dorothy Dewberry Aldridge: You asked if there were a lot of white people there. It was well integrated. And at the time, the mayor of Detroit, Mayor Cavanagh, was a white person. So there was no conflict between Blacks and whites as such. No.

Bill Kubota: One Detroit spoke to the late Reverend Dr. Joann Watson just before this year’s Detroit walk.

Rev. Dr. Joann Watson, Civil Rights Activist: It meant a lot because the injustice that was happening around the country was not just in the South. It also included the north. There were housing issues, employment issues, issues just related to the quality of your life.

Dorothy Dewberry Aldridge: In 1963, of course, there was the question about police harassment, police brutality of the young people in Detroit. Now, one other thing I want to add is that Medgar Evers had just been killed in Jackson, Mississippi.

Bill Kubota: Medgar Evers, an NAACP official, assassinated by a white supremacist less than two weeks before.

Ken Coleman, Detroit Journalist and Historian: And it was a motivating force that caused people to come out to the march that may not have had Evers not been killed only days before.

Jamon Jordan, Historian, City of Detroit: That march was organized by the Detroit Council for Human Rights, which was led by Reverend C.L. Franklin. And of course, if you don’t know C.L., you probably know his daughter, the Queen of Soul, Aretha Franklin. Reverend Albert Cleage, who would become the founder of the Shrine to Black Madonna and change his name to Jaramogi Abebe Agyeman. Benjamin McFall, the owner of McFall Brothers Funeral Homes and James Del Rio, who would go on to become a judge.

Ken Coleman: Reverend Cleage and Reverend Franklin decided to start the Detroit Council for Human Rights with the idea that there really hadn’t been enough improvement for African Americans since the 1943 race riot and the March, the Walk to Freedom, was the first major event that the organization organized.

Bill Kubota: The local NAACP not in on the planning. Seemed to them these activists were pushing too hard, too fast.

Ken Coleman: Some thought that Reverend Cleage was clearly more radical than the Detroit NAACP, and at times so was Reverend Franklin.

Bill Kubota: The NAACP did bring protest signs, but the United Auto Workers union was a real driver of the march.

Ken Coleman: There’s no doubt that the Walk to Freedom could not have happened without the UAW under the leadership of Walter Reuther.

Gavin Strassel, UAW Archivist, Reuther Library, Wayne State University: These are some really cool objects from the march.

Bill Kubota: UAW archivist Gavin Strassel sits on a wealth of research material at the Walter P. Reuther Library at Wayne State University.

Gavin Strassel: The records really reflect that as figures like Martin Luther King start to make inroads in American society, you can see that the UAW takes notice and becomes a major financial contributor and supporter of the civil rights movement.

Bill Kubota: Dr. King spoke before the union’s membership two years before the march. The UAW’s was Lillian Hatcher was a Walk to Freedom organizer.

Gavin Strassel: I think having the UAW involved in the planning probably went a long way in letting Martin Luther King know that this is a legitimate event and that this is something that he wants to take part in.

Ken Coleman: So Reuther and King had a great bond. In fact, there is some thought that King might have written some of the “I Have a Dream” speech at Solidarity House, UAW’s headquarters in Detroit.

Bill Kubota: So with the UAW and Reverend C.L. Franklin, there was Dr. King’s other Detroit connection.

Ken Coleman: Berry Gordy Jr., the founder of Motown Records, had met King, we know several years before 1963, probably the late 1950s.

Robin Terry, CEO, Motown Museum: And what came from that was Berry Gordy actually covering payroll for Dr. King to pay his staff. And my understanding is that happened more than once. So in so many ways, not only was Motown organically helping the civil rights movement and being a catalyst for bringing people together, but also in a very intentional way, they were supporting the efforts of Dr. King.

Bill Kubota: The Detroit speech at Cobo Hall, preserved on record by Motown.

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.: Segregation is wrong because it is nothing, but a new form of slavery covered up with certain niceties of complexity.

Bill Kubota: Dr. King would finish his speech in Detroit with the words, perhaps he’s most remembered, “I have a dream. Free at last.” Words he’d take to Washington two months later.

“The March,” 1963, National Archives: They came from Los Angeles and San Francisco. They came from Cleveland, from Chicago-

Bill Kubota: And they came from Detroit. August 1963, the March on Washington. Detroiter Edith Lee-Payne was there with her mother.

Edith Lee-Payne, Marched in Detroit and Washington, 1963: She decided that we would go to Washington. She would always stress to me how important it was for me to be the best that I could always be, and I could achieve and be whatever I wanted to be. It helped me be more of an American, which is what I am. The fact that I’m a Black American is secondary. That doesn’t define me, and our color should never define us. Dr. King didn’t want our color to define us. He wanted our character to define us and who we were as a person.

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.: And in Birmingham, Alabama, and all over the South and all over the nation, we are simply saying that we will no longer sell our birthright of freedom for the mess of segregated parties.

Ken Coleman: Historians have written and said often that had there not been those two marches, we may not have achieved the 1964 Civil Rights Act and the 1965 Voting Rights Act. Without those marches which take place just before the passing of that landmark two pieces of legislation.

Stay Connected:

Subscribe to One Detroit’s YouTube Channel & Don’t miss One Detroit Mondays and Thursdays at 7:30 p.m. on Detroit PBS, WTVS-Channel 56.

Catch the daily conversations on our website, Facebook, Twitter @DPTVOneDetroit, and Instagram @One.Detroit

View Past Episodes >

Watch One Detroit every Monday and Thursday at 7:30 p.m. ET on Detroit PBS on Detroit PBS, WTVS-Channel 56.

Stay Connected

Subscribe to One Detroit’s YouTube Channel and don’t miss One Detroit on Thursdays at 7:30 p.m. and Sundays at 9 a.m. on Detroit PBS, WTVS-Channel 56.

Catch the daily conversations on our website, Facebook, Twitter @OneDetroit_PBS, and Instagram @One.Detroit

Related Posts

Leave a Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked*